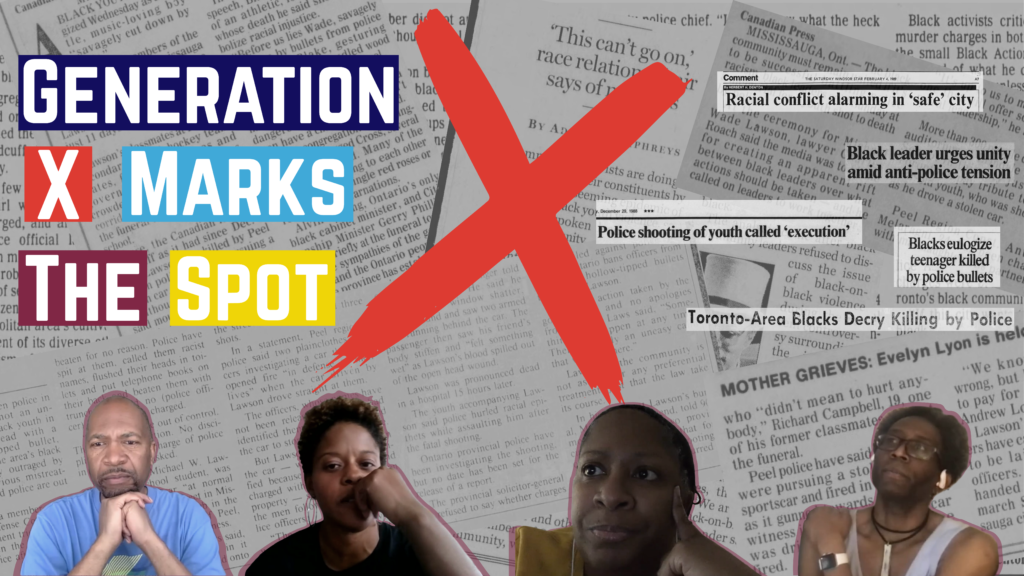

What four Gen X’ers did to activate and co-create a new kind of Caribbean-Canadian culture in Toronto

Full Audio Documentary

Writer and Director: Dayo Kefentse

Research Assistant: Jonsaba Jabbi

Audio Producer: Adam Power

When English rockers The Who’ released their hit “My Generation”, they knew who they were talking about. It was the fall of 1965, and Baby Boomers like them were coming of age — taking over the world.

It was in that same year though, 1965, that Generation X made its debut.

Described by the Pew Research Centre as a demographic distinguished by people born between 1965 and 1980, this group, like most, share some common experiences.

“I mean, when about Generation X I think, like the technology, I think about is like the microwave, VHS cassettes, The Cosby Show. In terms of world politics, the Reagan era. Mulroney. Two working parents, latchkey kids”. Heather Infantry said.

“Apple computers! The car phone”, Shawne Gray interjected. “Pager, Pagers”

“Rap music…is our generation!” said Infantry.

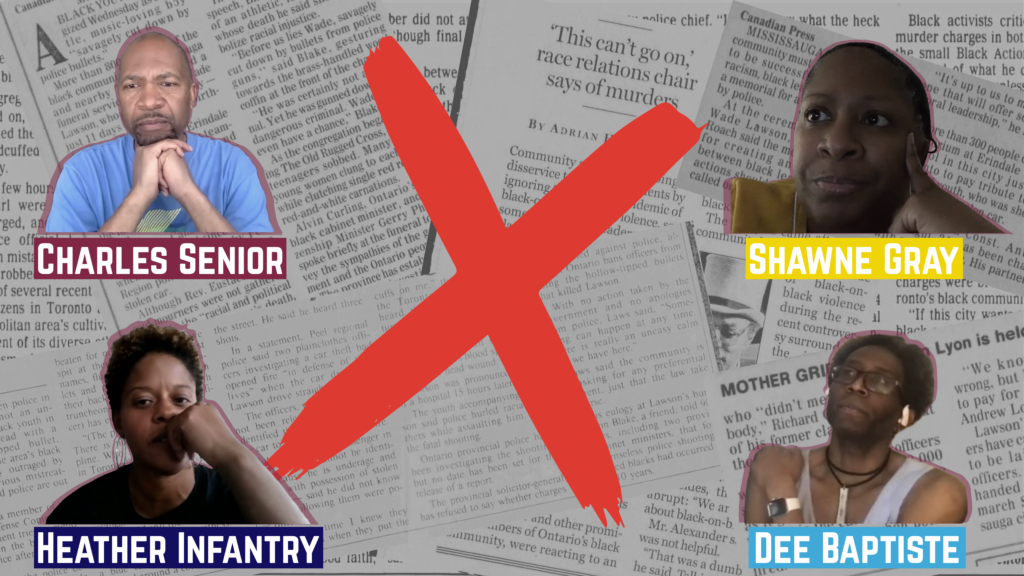

Heather Infantry and Shawne Gray were comparing notes on what connects Generation X. On a sunny day in May, they were joined by Charles Senior and Darren Baptiste who now likes to be referred to as Dee. They met with DM&C Founder and Managing Director, Dayo Kefentse, to reflect and reminisce about their younger days.

They’re now in their 40s and 50s. But back in the day, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, they were part of a growing group of young Caribbean-Canadians who were coming into their own and creating a distinctly unique Canadian culture. This whole group was serious about making a change.

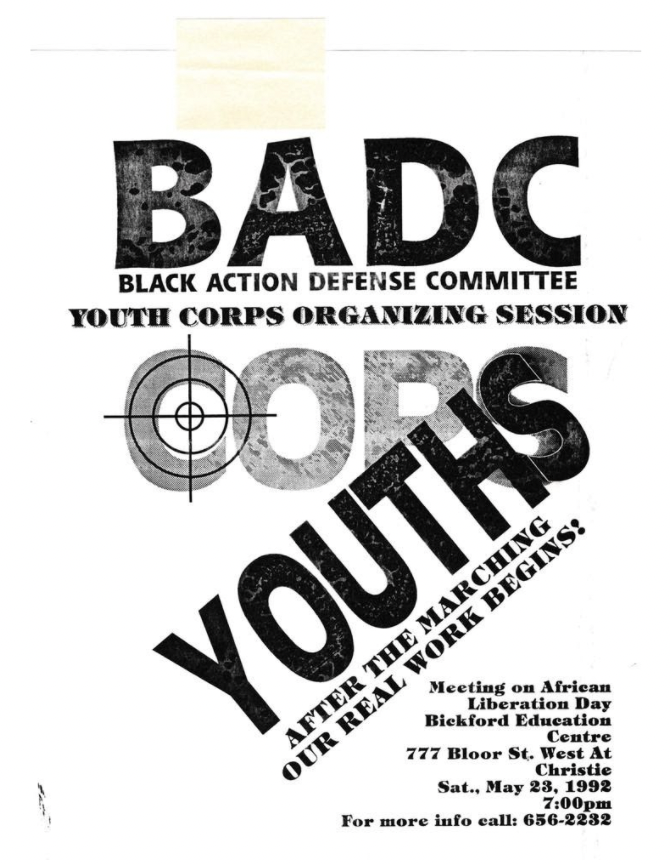

On the radio during a time when Canadian music rappers like Maestro Fresh Wes were hot, Heather, Shawne, Charles and Dee were part of the Black Action Defense Committee. They were on the youth team. A generation of kids of Caribbean parents who came up to Canada in the 1960s and 1970s.

Borders were opening wider due to labour shortages and changing immigration laws. A ‘points’ system was put in place as a scheme to boost Canada’s labour shortage. Domestic servants, car porters and young professionals were arriving from the Caribbean and other Commonwealth countries to build a new life.

For Caribbean-Canadian kids who were either born in Canada or those who arrived in Canada as children, the concept of ‘home’ could get a little confusing.

“A number of people my age or with my circumstance, say the Gen X’ers who were born here, is that we believe we can go back home, right? We believe we are Jamaican. And even a lot of the Gen Y’ers believe they’re Jamaican, and we can go back home not realizing that ain’t nobody looking at you as Jamaican, right?” Charles laughed. “We have almost a false sense of who we are, where we belong, or where we’re accepted, maybe. Maybe that’s better. But we’re really situated here. Our roots have started someplace else and then we are replanted here. But the follow-up to try and understand that, is a little bit different, right? It takes a little bit of time for a lot of us.

As much as it took me a long time to admit I’m Canadian, right?. I’m Canadian with Jamaican background, and I’d say that acknowledgement didn’t happen till probably into my late 20s, mid 30s.”

As Gen Xers we swing between three different types of realities: we are Canadian citizens, who are also uniquely connected and rooted to our Caribbean culture through our home base. We are also acutely influenced by the media powerhouse that is the United States.

And that U.S. culture? When Gen Xers were growing up it came in waves, both good and bad.

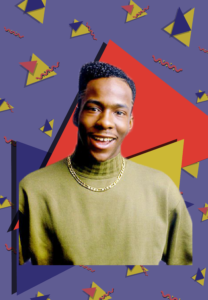

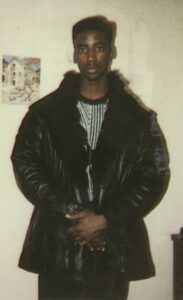

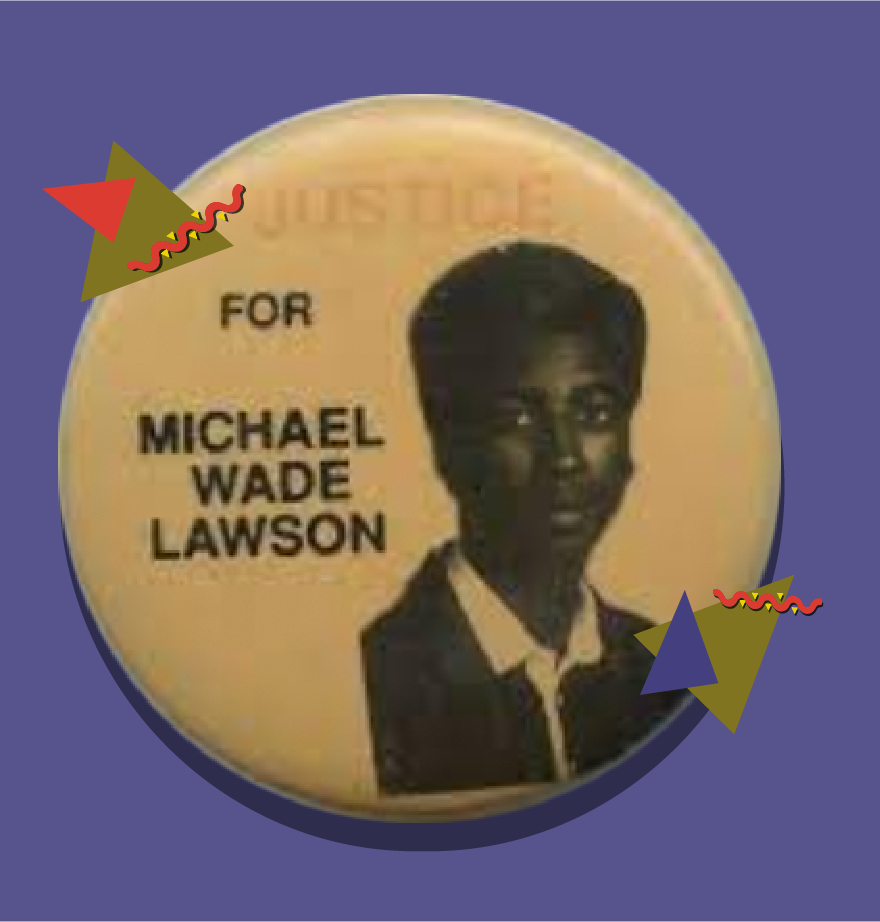

Michael Wade Lawson was driving a car that was reported to be stolen. A few hours later, he was shot in the back of the head by police.

He was just 17-years old.

News reports would later reveal that the bullet that killed him was a type that was banned for use by police in Ontario.

This was one of many details that the youth of the Black Action Defense Committee (BAD-C), started to dig into.

Nothing though could be done without the blessing of the organization’s elders.

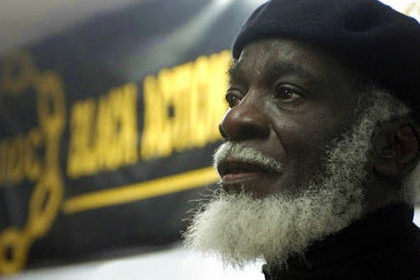

One being Dudley Laws:

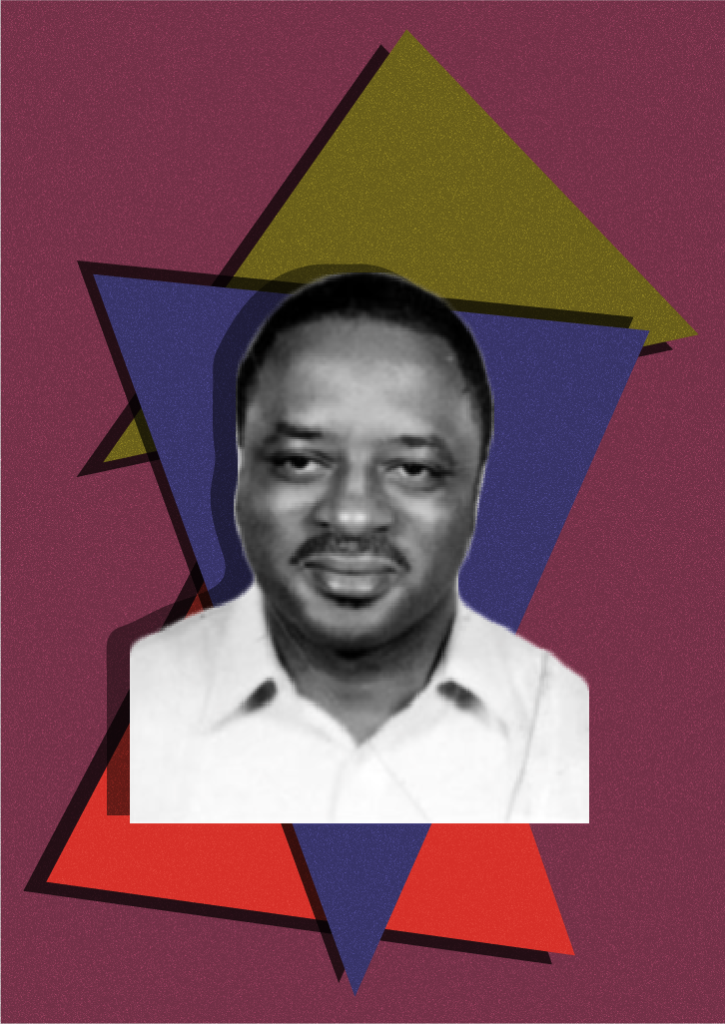

And the other being Charles Roach:

“I think that the word that comes to mind is consistent, right?” Charles Senior recalled. “Consistently working for and advocating for Black People against the system that was oppressing Black people, and you know I don’t want to say one system, but a variety of different systems.”

Dudley and Charles weren’t the only two elder activists in the group. Others like Sherona Hall, Lennox Farrell, Akua Benjamin, Monifa Younge and Dari Meade, were also fighting against the systemic brutality that was happening to Black people in those days. They typically got the spotlight…as most elder leaders do.

Meanwhile the youth, well, their contributions were left untold. Until now.

It was time for them to speak up. Michael Wade Lawson’s death in 1988 hit close to home. Because unlike previous shootings which were equally tragic, this was one of their peers. One of our peers. Another Gen Xer. Another young Black person growing up in Canada in the 1980s. Canadian, with a mix of Caribbean culture, spiced with a slice of Americana.

Looking at him, he could have been a boyfriend, a brother, a cousin, a best friend.

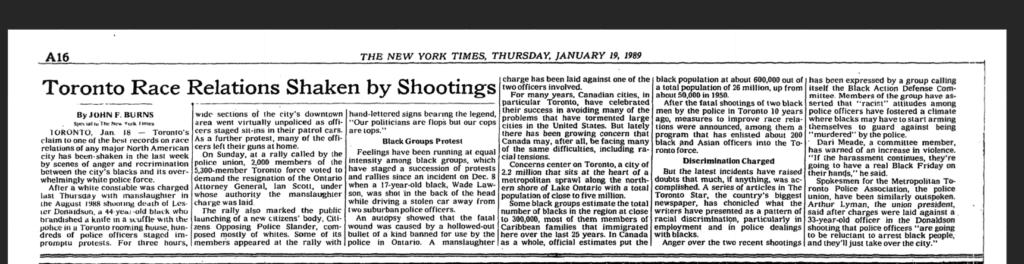

And he died in a way that up to this point, we had only heard about in US magazines and news features. Toronto’s Black community was changing. And the world was starting to notice, as demonstrated by an article in a January 1989 edition of the New York Times.

Police unions were feeling the swell and growing influence of the Black community after multiple protests, including one for Lester Donaldson – another Black man that was shot in 1988 by police. He was 44 years old. Ontario police perhaps had reason to be concerned: new eyes were on them.

Four days after Michael Wade Lawson’s shooting, the Solicitor General for the Province of Ontario announced they were striking up a new group. Called the Task Force on Race Relations and Policing, it was looking into the police training, policies, practices and attitudes as they related to visible minorities in Ontario.

These young activists helped push that. These young activists were definitely making a difference.

As 1989 rolled on, Bobby Brown’s ‘My Prerogative’ was a worldwide hit and Shawne Gray was looking forward to her 21st birthday. Charles and Dee were also in their early 20s. Heather, the youngest of the four, was in her mid-teens. They were at a stage when, as Bobby would say, they wanted to make their own decisions. And they decided to be there for Michael Wade Lawson.

“I went to the trial,” Shawne Gray revealed. “I went to the Wade Lawson trial because I said I can’t trust what they’re telling me. I’m gonna go and listen for myself. And that was the first time I had gone to court or gone to trial or anything. And so I was there, like you know, taking notes. Because I’m like: this is not what they’re saying in the news.”

“Part of the reaction in the community was: let’s go blow up some police cars and let’s go, you know burn, burn it down. Burn, burn everything down,” added Dee Baptiste. “That prompted me to write a booklet, a pamphlet that I called ‘What if we all killed a cop’? And it was sort of like in my mind, the logical progression of what would happen if somebody did go and do that. Or the group started to go and do that. I handed out (the pamphlets) all over the place. The largest place I handed out was at a Public Enemy concert. That just naturally built into a bunch of people saying: Oh let’s, let’s start writing about these issues.”

Since cell phones weren’t yet commonplace, home numbers had to be used to contact the young activists.

“When it was passed out the police kind of found out who we were, and did a little scare campaign in terms of having their police officers outside of our houses. shared Charles Senior. “You know, unmarked cars, two people sitting down there all the time and stuff like that.”

“I used to love the police escort home from BADC, right?” laughed Shawne Gray.

Toronto streets in the late ‘80s, early ‘90s were a little bit quieter, but places like Third World Bookstore on Bathurst Street was always buzzing. The owners, Leonard and Gwendolyn Johnston, provided a safe space for youth to discuss, share and organize.

They were busy in those days: designing flyers to be shared at early rap concerts in Toronto. They also used the space to promote protests, vent, plot and monitor.

In those pre-digital days, these were some of the ways in which young Black GenXers were doing activism.

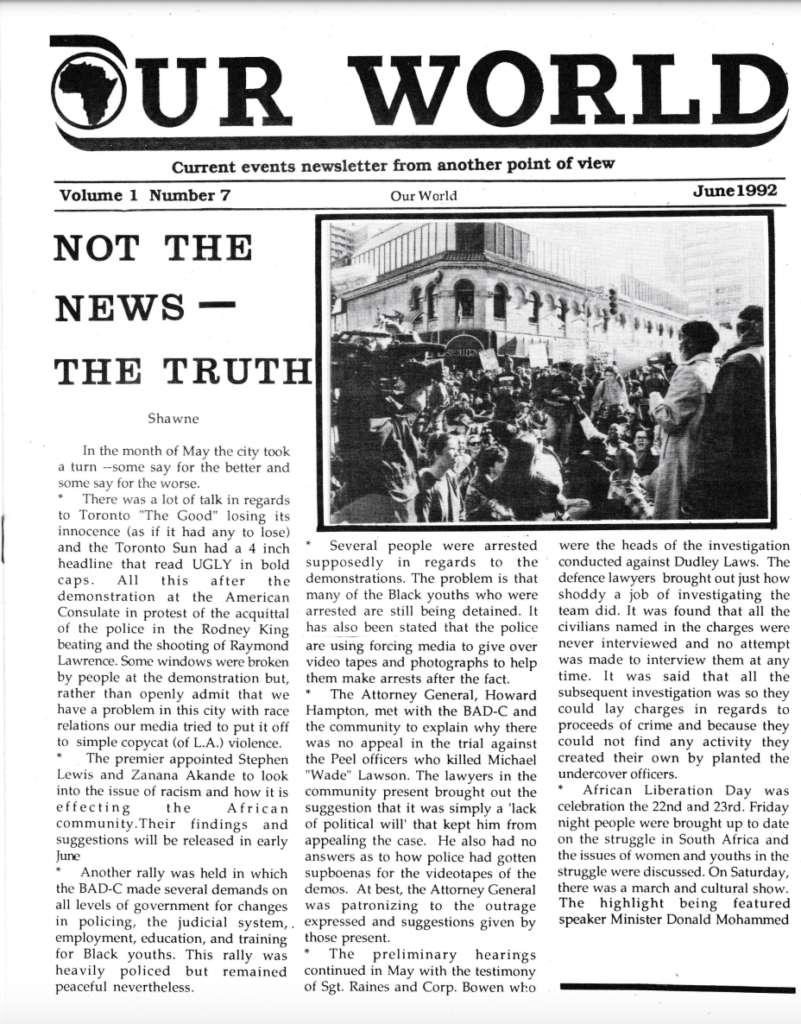

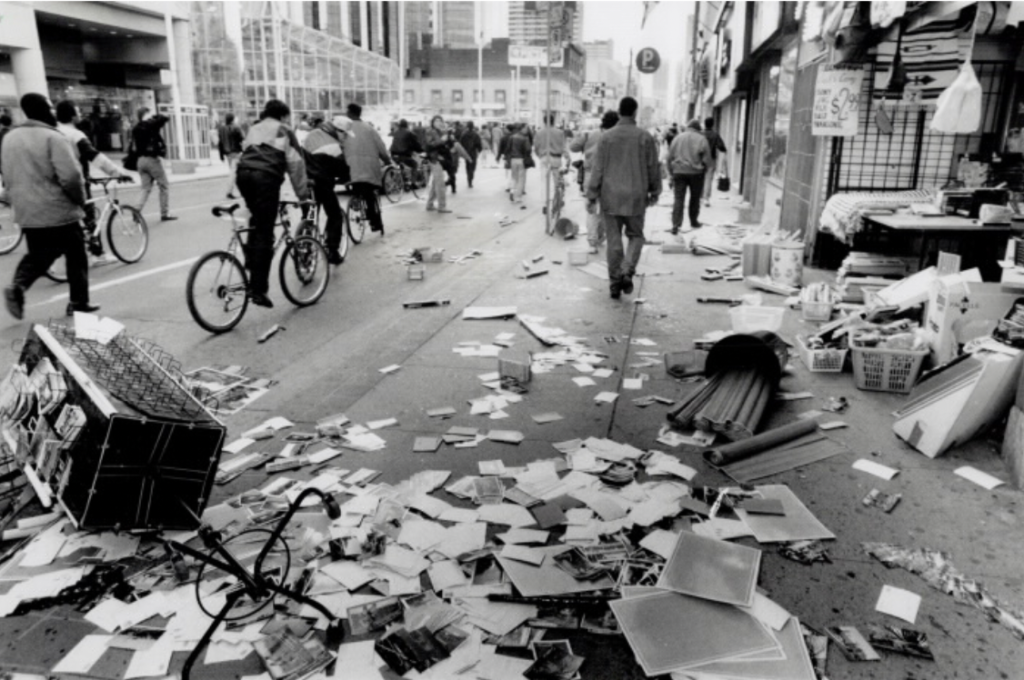

And then, on May 4, 1992, activism had a different sound. For anyone coming up in Toronto in those days, May 1992 is a month and year that is hard to forget. It’s the day that Yonge Street in Toronto was ripped into shreds.

What started out as a peaceful protest organized by the Black Action Defense Committee turned into what media outlets labelled as a riot. Nearly 30 years later, many now see those same acts as an uprising.

While opinions differ on what triggered these acts on Yonge Street, most believe it was a reaction to the acquittal of the white police officers who were videotaped while assaulting Rodney King – a border and miles away in Los Angeles

Others will argue, the Yonge Street riot, or uprising, was sparked after the shooting death of another young Black man. This time Raymond Lawrence who was 22. He was killed by Peel Police.

Within weeks of that shooting, the cops who killed Michael Wade Lawson were acquitted.

So by May 1992, that spring, Black youth in this city – including the youth of BAD-C – had had enough. They were watching how their elders – Dudley Laws and Charles Roach and others – were handling the aftermath of the events on Yonge Street, and they were frustrated. They made their views known in what they called a Manifesto.

Here is some of what that said:

Charles, Dee, Heather and Shawne kept that Manifesto and a series of other documents from that era. Dayo asked who authored the Manifesto:

“Dee did it!” laughed Shawne Gray

“I love this, I love this!” exclaimed Heather Infantry

“It reads like some shit I’d write,” admitted Dee Baptiste. “Oh yeah, yeah it was not even shut down, it was just disregarded. That’s how I remember that.”

“Dudley was just like this is not happening!” laughed Shawne

Dayo wondered, “Did you feel as young people that you were disregarded? Or disregarded in terms of your efforts?

“I don’t think we expected things to change the result of us handing stuff in. I mean you kind of knew where things stood,” shared Charles. “I think we got the reaction that we expected in terms of you know, this ain’t gonna happen right? I think when we got that we were like: ‘Okay, I think we’re good with it’. There wasn’t like any hard feelings or anything like that.”

“I remember when. Dee was like, “What are we doing?”, remembered Shawne. “ (We thought) We’re not doing anything and we’re not saying anything. We were going to lose our relevance and so he wrote this.”

Shawne remembered more details.

“I remember being sat down by Dudley in his office, with Dee, can’t remember if Charles was there. And we were like told all the things that was wrong with this (Manifesto). And why, why it can’t happen. And I think at that time too, probably shortly after that, that Dee and Charles and myself kind of separated from BADC and kind of went another way. I think we just didn’t think the response was strong enough. We were like, whatever BADC was doing officially at the time, we thought it was like pussyfooting around. (BADC wasn’t offering) a strong enough response to what was happening.”

“One of the things that they got from us (youth) was they got more from us than they wanted, right?” remarked Charles. “What they got was a lot more than they bargained for. One of the things that that you know pissed probably a good amount of the BADC committee off is the advocating for putting Dari (Meade) in front of media more or in front of leadership more.”

“We knew that Dari honoured a lot of people who think similar or close to us that were seven, eight years older than us, and seven, eight years younger than us, and could have galvanized those people together,” Charles continues. “And the, the good work that Dudley was doing was, was uh going to be great for those 47, 48 years old and up right. But for the energy of the young people, it should have been Dari who could have really galvanized a lot of stuff moving forward.”

“What we experienced is, is almost cliched and in terms of generational struggles passing on of the torch inside of organizations, community based organizations.“We experienced nothing unique in clashing with the existing leadership and us wanting to go a different path. And it’s natural it’s good I mean you know, otherwise we would have been doing the exact same thing, but new people new ideas, that’s great.” remarked Dee.

“But Dari sat me down one time and we had this long conversation about where things would go. An he explained to me very clearly that you can’t put somebody into the leadership position: leadership is not given, it’s taken. You have to take the mantle of leadership. If you want to lead the organization, you have to put in the work to go out there and do the hustle. That’s, that’s all it is: who hustles the most, gets most, gets the most. And there’s no way you could out-hustle Dudley. You just couldn’t. His ability his willingness to sacrifice his commitment to it and his ability to focus his entire life, he built his whole life: his income streams his everything he built it around being able to do what he felt he needed to do for the community.

So, if you want to take the leadership from him, you have to go and do more than he is doing. You have to go and sit with the mothers of victims, you have to go and sit in on inquests, you had and be at the police station when somebody was locked up or being released. It’s never going to make the newspapers, but you had to go and do that.”

“You know, Dudley had done that altruistically to get it done but a lot of times that sacrifice to the family doesn’t always come altruistically. Sometimes it comes from a push from the system and the forces that are in the system.” pointed out Charles. “I’d say Dee experienced (sacrifice) way more than Shawne or I ever did, within the movement, But that (level of sacrifice), honestly, nobody knows right? Really and truly, very few people if any know.”

As time has moved on, new generations have started looking for likes — for social media attention for what they’ve done and accomplished. This group is a bit more old school — it seems they did what they did for the love of community. Dayo wondered if they thought they had gotten enough credit for their work since, for the most part, their contributions had been hidden and locked up in bins in basements.

“You know we all play a role in different sense to try and get things met. So those names, whether it’s Lloyd McKell or Heather Infantry or whoever, those names are doing work to try and make sure more people get to the point of…you know the movement that we saw and that we’ve been seen over the last three, four years. And prior to that,” said Charles. “So there’s a number of things that that you do and we move from the angry Black person role in a meeting or or in a space to you know the practical critical thinker, knowing how to get stuff done and pushing young people in terms of thinking twice to make sure, things are correct, before moving forward. We play different roles in the struggle, as time moves on.”

It may be a bit too early to talk about their legacy since they are all in only in their 40s and 50s. When asked they modestly believe the “legacy” title is for readers or listeners to this story determine.

But when pressed, Heather and Dee offered some final thoughts:

“I would hope that the legacy would be for those that are coming after that there has been a long dragged out fight and maybe they don’t have to fight anymore.” shared Heather. “Maybe they can just chill the fuck out, knowing that others will continue to be sacrificed. But yeah, we’ve earned the right to just rest. And there’s great power and there’s great resistance in resting.”

Dee added a final thought.

“I just want people to realize that we brought our whole selves to the game and that’s what you have to do. To be effective, you got it you got to be in it to win it, right? That’s what we did. And it’s not done.”